On January 4th, 2017, legal professor and noted sports law scholar Nathaniel Grow wrote about a relatively obscure section of California labor law that purportedly gave Major League Baseball’s Mike Trout the ability to become a free agent in 2017 despite a contract extending until 2020. The law in question—California Labor Code § 2855—does not limit itself to baseball, and would apply to the NHL as well. The potential for players to become free agents after seven years would temporarily upend the NHL as elite franchise players hit the market years earlier than expected.

Section 2855 of the California Labor Code—more commonly known as the De Havilland Law—prevents the enforcement of an exclusive personal service contract after seven years, regardless of contract length. That means that after the seventh year of a contract, an employee may opt-out without repercussion. Personal service contracts include athletic contracts, so any California-employed NHL player with a contract longer than seven years could use the De Havilland law to enter into free agency after seven years.

An even broader interpretation says that the seven consecutive years of employment can come from both one long contract or multiple extensions. A California court ruled that numerous contract extensions did not reset the clock for the law’s purposes. This interpretation greatly expands the player pool eligible for earlier free agency. An 18 year old NHL player who first signs a three-year entry level contract (ELC) before signing an extension could potentially reach free agency as early as 25—two years earlier than most players. Under this liberal interpretation, a contract extension would extends the original contract rather than create a new contract, even if the material terms change.

Who is Affected?

Because De Havilland’s law is a California statute, it only applies to California-based employees and employers. Assuming the NHL’s California-based teams are considered California-based employers and subject to California labor laws (more on that later), the three NHL teams affected are the Anaheim Ducks, the Los Angeles Kings, and the San Jose Sharks. The AHL teams potentially affected are the Ontario Reign, San Jose Barracuda, San Diego Gulls, and Bakersfield Condors. Most AHL players with AHL-only contracts, however, sign one- or two-year contracts and are not affected.

I have laid out which players could take advantage of De Havilland’s law below, divided into the conservative and liberal code interpretations discussed above. The liberal interpretation will include more players by default because it expands the pool of players eligible to take advantage of its opt-out provisions. You may notice that I have omitted players that have played with an organization for more than seven years. Many of those omissions stem from extensions signed after the player’s contract expired. Any RFA that signs after July 1st should reset the clock even with a more liberal interpretation of De Havilland’s law. Because there is a period of time that the player was without contract, any subsequent signing creates a second distinct employment period rather than continuous employment. [note: this point isn’t guaranteed. A court could rule that because the RFA process restricts a player’s movement by forcing teams to compensate former teams when they sign RFAs away, it doesn’t constitute full free agency under the statute.]

Finally, two players—Jeff Carter and Brent Burns—were traded midway through one of their contracts. To take advantage of De Havilland’s law, however, you must start counting from the player’s first full season playing in California.

Team Affected

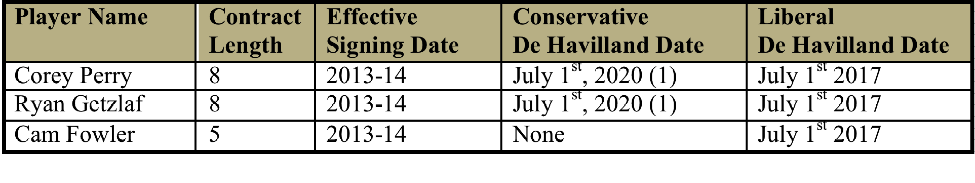

Anaheim Ducks

Under the conservative interpretation of the De Havilland Law, both Corey Perry and Ryan Getzlaf could opt out of their contracts at the end of the 2019-20 season—one year before the contracts expire. Under the more liberal interpretation, Perry, Getzlaf, and Cam Fowler could all become free agents at the end of this year. The Ducks have the least number of players potentially eligible to take advantage of the De Havilland law, but all players eligible are core guys.

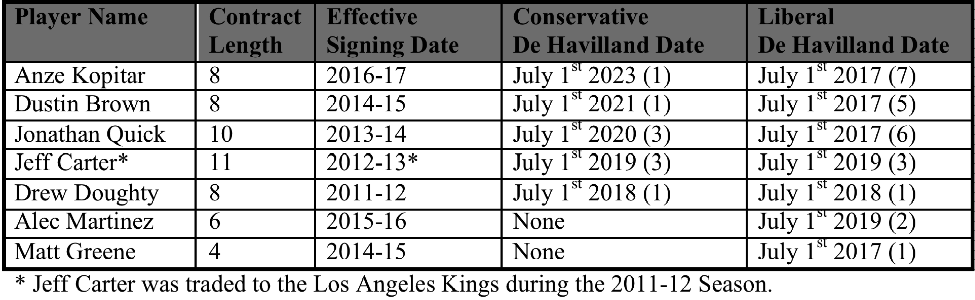

Los Angeles Kings

The Kings have the most players potentially eligible to use the De Havilland law to opt-out of their NHL contracts early. Five players, including Anze Kopitar, Dustin Brown, Jonathan Quick, Jeff Carter, and Drew Doughty, could all opt-out in the future under the law’s conservative interpretation. Doughty could opt-out as early as next year, and Carter as early as the end of the 2018-19 season. A broader reading would include defensemen Alec Martinez and Matt Greene.

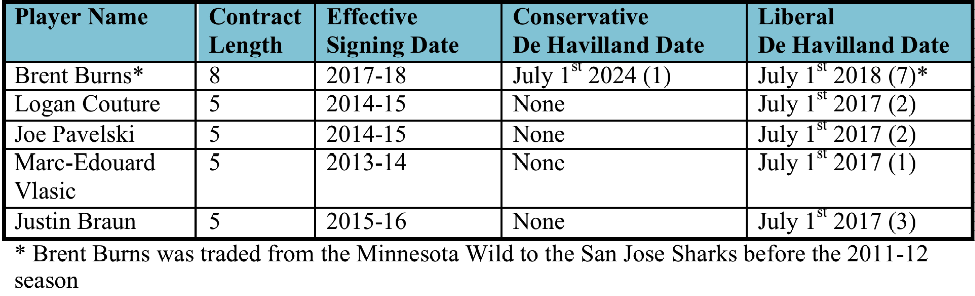

San Jose Sharks

Under the law’s conservative interpretation, the Sharks have little to worry about for the foreseeable future. Only Brent Burns could opt-out of his contract under the conservative interpretation, and even then not until the end of the 2023-24 offseason. If courts accept the liberal interpretation, however, the Sharks could lose their core. Logan Couture, Joe Pavelski, Marc-Edouard Vlasic, and Justin Braun would all be eligible to opt-out this summer, and Brent Burns could follow next summer.

Overall eight players in the entire league could potentially opt out of their contracts under the labor code’s conservative interpretation, and an additional seven could opt out under a more liberal interpretation. And while we assume each player becomes a free agent at the end of a particular season, a strict reading of the law could allow a player to opt-out midseason as soon as he hits seven calendar years into his contract.

Barriers

De Havilland’s law seems to work—in theory. In practice, however, NHL players face numerous barriers to early free agency. First, the law has never been used by a labor union, making it unclear whether the law trumps a collectively-bargained employment agreement such as the NHL CBA. Second, it is unclear whether California law applies—even in the context of California-based players. Third, the costly and lengthy litigation required to resolve the expected legal dispute make the law impractical for most NHL players. Fourth, it is unclear if any team would—or could—sign a player who successfully opts out of his contract under § 2855. Finally, a player risks harming his reputation by unilaterally breaking his contract for more money.

The first barrier is whether a collectively-bargained agreement overrides state labor laws. The lawyerly answer is “maybe.” De Havilland’s law has never been challenged by a union, so no court has ever attempted to rule on that issue. Both sides would have to look to how courts treat CBAs in conjunction with other labor laws, and the answer varies. Without getting into the legal nitty-gritty—which is outside the scope of this article—the law is muddled and no clear answer exists. It would be one of many issues litigated by both parties.

The second barrier is whether California law even applies at all. De Havilland law’s applicability depends on whether California law applies. Many non-hockey contracts have what’s called the “choice-of-law” provision that specifies which State’s (or Province’s) laws apply to the parties. Thus, even though both sides do business in one State, a contract can dictate that another State’s laws would apply. The CBA and the included example SPC, however, are silent as to choice-of-law. That means that it is up to a Court to decide if California law applies. Now, it may seem obvious that California law binds California teams, but the NHL would have some cognizable legal defenses, including the fact that because the NHL is headquartered in New York, New York law should apply.

The differing legal arguments foreshadow the third barrier—litigation takes a long time. Because this issue is a novel one for courts, and both parties have much at stake, a final determination may take a while as the litigation winds itself through the various court levels. One saving grace for players, however, is that the contentious issue is purely legal. A decision resting on legal argument rather than a drawn out trial alone should significantly hasten the litigation pace.

Assuming that the law applies to California-based athletes—and a player becomes a free agent—the NHL might bar another NHL team from signing the new free agent. The CBA dictates what a free agent is, and dictates how long a team holds a players right. The NHL could refuse to approve any contract with the quasi-free agent because while California law says a player is a free agent, he is not eligible to join another team under the CBA. The CBA does something similar with free agents playing overseas. When an overseas free agent attempts to join the NHL after January 1st, the player must clear waivers.

The player would remain a free agent, but he’d have to find employment outside the NHL. Because the NHL represents the pinnacle of hockey for most players, any move outside the league would be lateral at best. And while refusing to sign free agents would constitute an antitrust violation, league employment action is usually exempt from antitrust laws because they do not usually apply to collective bargaining agreements.

Finally, this analysis cannot ignore the human element. The NHL remains one of the more traditional sports leagues. Players do not like to rock the boat for fear of being labeled a “troublemaker.” So in a league where flashy goal celebrations cause mass hand-wringing, a player unilaterally becoming a free-agent outside the CBA rules would draw ire across North America. Players waiting for better contracts as RFAs already garner criticism from all corners, even though they are well within their rights. Imagine the reaction by certain fans and media if a player goes one step farther to secure a more favorable contract.

Ideal Candidates

The narrow scope of the law coupled with the above barriers creates a very small pool of ideal candidates. Not only candidates, however, but narrow scenarios where using the De Havilland law makes sense. For example, declaring free agency during a lockout or after a CBA expires could avoid the issues the CBA poses to this law because the CBA no longer applies. A Restricted Free Agent could also be a good test case if the RFA was earning drastically less than his market value. The significant increase in salary could serve as motivation to overcome the above-mentioned barriers. Finally, a player languishing in the minors near the end of his career—or a goalie relegated to a backup role—could seek a new locale elsewhere.

Final Thoughts

Maybe the De Havilland law is just a legal curiosity. Player relations in professional sports right now are more harmonious then ever as both players and owners are flush with new TV money. The NBA and MLB just negotiated new CBAs without threatening any lockouts or strikes. The NHL looks to follow suit if they can settle their escrow disagreements amicably. Basically, this may not be the right time to test out De Havilland’s law in the NHL. But all it takes is one disgruntled NHL player on a California-based team to potentially upend the NHL. One underpaid RFA with no legitimate offers on the table. One breakout player in the midst of a long-term deal.

We may never see an NHL player test De Havilland’s law, but the thought of many skilled players immediately reaching free agency all at once is enough to make any fan salivate at the possibilities. Who wouldn’t want to imagine Brent Burns in their favorite team’s colors?

That’s ridiculous. These players willingly signed theses contracts.

The law says otherwise. De Havilland’s law has been used to sever long contracts between actors/actresses and movie studios for decades. And for some players, they are forced to sign deals with teams as RFAs because GMs rarely issue offer sheets.

Damn if the Angels lose Trout and Ducks lose Perry and Getz than I don’t know if I’ll be able to live through the depression

Hopefully Pujols will take advantage of that in year 7 of the 10 year deal ;)

Hard to imagine them doing this.

Typical progressive professor and typical stupid progressively liberal and socialistic California.

Fortunately the rest of the country isn’t as stupid as Ca. I know. I live here.

And I would bet my house it will never even see the light of day outside this article.

It was actually pretty common in the entertainment industry.

link to en.wikipedia.org